Tucked away in St George’s Church, Shadwell, is a small exhibition about Women in the East End. Amongst them, Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960) is well known; Edith Ramsay (1882-1983) is not. Both women came to the East End from comfortable middle class backgrounds, committed themselves to the people there, worked hard to improve difficult conditions and embedded themselves in the community. Through their lives, we can get an understanding of what the East End and Dockland communities were like in the first half of the Twentieth Century, through two World Wars and their aftermaths, and gain an insight particularly into the lives of people there – most especially women.

Syliva Pankhurst. Source: Wikipedia

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst was born in Old Trafford, Manchester. Her father, Dr Richard Marsden Pankhurst, was a progressive lawyer, an advocate of women’s rights and women’s suffrage and a Fabian Socialist. His strong socialist views were to influence Sylvia throughout her life. Her mother, Emmeline, was an active campaigner for women’s suffrage and founded the WPSU with Sylvia’s eldest sister, Christabel, in 1903. It was work for this organisation that sent Sylvia to the East End in 1912.

The East End had a well developed and active interest in the suffrage movement already as well as a proud tradition of active campaigning, protest and support for the Labour cause. Sylvia was a charismatic speaker but she was supported by a network of local women whose names are less well known. Melvina Walker was a docker’s wife and a former ladies maid: Julia Scurr, born in Limehouse, had been elected as a Councillor for Poplar and a Poor Law Guardian. Mrs Savoy was a brushmaker in Bow, Jessie Payne worked with her husband as a bootmaker: Adelaide Knight from Bethnal Green, had been made secretary of the Canning Town WSPU Branch in 1906. Disabled and married to a black seaman, she suffered police brutality and imprisonment for civil disobedience. Like Sylvia and many others she was prepared to sacrifice her liberty, and her health, for The Cause.

Sylvia wa shocked by the conditions and deprivation she saw in the East End:

“Women in sweated and unknown trades came to us telling their hardships :rope-makers, wasre rubber cleaners, biscuit packers…those who made wooden seeds to put in raspberry jam. Occupants of hideously unsavoury tenements asked us to visit and expose them. Hidden dwellings were revealed to us, so much built around them that many of their rooms were dark as night all day……”

Her concern for the East Enders was not shared by her Mother and Sister; Sylvia’s opposition to the War, her high profile campaigning, her loyalty to “her mates” in the East End and her fight to improve conditions there set her apart. The East London Federation of Suffragettes was formed quite separate and democratic, with a working class base and divorced from the WPSU.

The First World War hit the East End hard. A slump at the outbreak of War saw men unemployed in the Docks and the demand for goods produced in the East End, often made by women who were poorly paid and exploited, very much reduced. Food prices rocketed. Starvation was a reality. The ELFS response was a practical one setting up a cost price restaurant in their headquarters at 400 Old Ford Rd and offering free tickets, discreetly, to those who could not pay for the simple and nutritious meals. Milk Centres were set up in Bow, Canning Town, Poplar and Bromley to help starving infants. The Women’s Dreadnought – the ELFS newspaper – campaigned against exploitaion at work, food price rises, poor pensions and delayed allowances for soldiers’ wives and families.

There was a practical attempt to provide work for women with young children. The Toy Factory at 45 Norman Road, Bow, allowed for flexible working hours with reasonable pay and the prospect of childcare. Its products were sold at Selfridges. Mrs Payne taught bootmaking. A creche was set up with Lady Sybil Smith assissting and later expanded into a disused pub, The Gunmakers Arms. The Mothers Arms, as it became known, included the first ever Montessori School for older children and a medical centre staffed by two doctors and a nurse to deal with mother and child health issues.

Some of these projects were funded by well wishers and activists. Nora Smythe, an artist and sculptor, bankrolled the newspaper and the cost price restaurant. Her photographs of Sylvia and the ELFS activities are a valuable record of the East End at this time and are archived in Amsterdam, though now reproduced. While many of the actual buildings have disappeared, it is still possible to see the Toy Factory (now a private house) and follow the Suffragette story around Bow: Rosemary Taylor’s book “Walks through History, Exploring the East End” (2001) has an excellent trail.

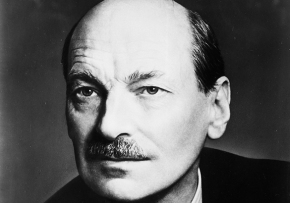

Dame Edith Ramsay M.B.E. Source: Gateway Housing.

Edith Ramsay does not enjoy Sylvia Pankhurst’s high profile. Her papers were archived at Tower Hamlets Record Office, Bancroft Road at her death. Her friend and fellow Councillor, Bertha Sokoloff, produced a biography entitled “Edith and Stepney” in 1987. There are few photographs of her and her internet presence is very minimal. Yet Edith embedded herself in the East End community and had a tireless interest in everyone, working from 1920 when she arrived in Whitechapel until her death to improve living conditions, education, employment opportunities, health and welfare and community relations.

Born in Hampstead into a middle class family (her father was a Presbyterian Minister), Edith came to teach at the Old Castle Street Day Continuation School providing extened education for 14- 16 year olds on day release from their employment. Put up in the stark conditions of the Toynbee Settlement tenements, she had one very small room, shared “kitchen” on a landing, a pump in the yard and a shared WC. Baths were taken at the public bath house. Edith shared the lives and concerns of locals but was very aware that, though very basic, her living conditions were much better and more stable than many. This led her to visit and publish reports on hostel accommodation and doss houses in the Whitechapel area. Her reports document poor conditions, the division of families and the hand to mouth existence of the poor. Her particular focus was on women and children forced to live in poor and unstable conditions, thrown out on to the srteets during the day and sharing cramped, crowded and insanitary dormitory conditions at night.

From 1922-5, Edith became the Stepney Children’s Care Organiser with responsibility for organising voluntary helpers dealing with health care, free meals, clothing, milk distribution and child protection. In 1928, she returned to education becoming the Manager of Heckford Street Evening Institute where evening and afternoon classes were organised for mothers, workers and the unemployed. Adult Education was her paid job – it was the background and impetus to her immersion into the community and a life long commitment to improving conditions across the Borough for all.

Edith’s organisational skills and knowledge of the community saw her being made responsible for the evacuation of children, their families and old people in September 1939. She stayed in Stepney throughout the War